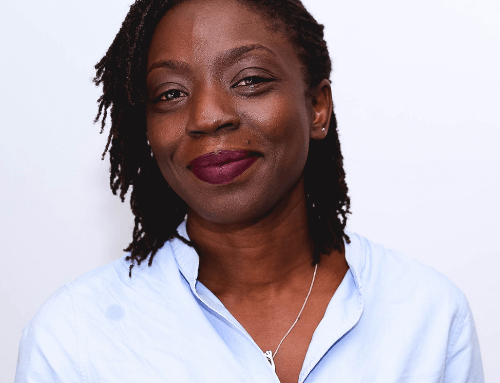

Jasmine Valle, Amref Health Africa in Canada

Menstruation is oddly viewed as one of the shameful secrets of women’s health. It is stigmatized and often misunderstood. The shame and embarrassment of menstruation often affects a young girl’s confidence and desire to go to school, get involved in extracurricular activities, and her general self-esteem. Poor menstrual health can also lead to other reproductive health complications, which also affects a girl’s wellbeing.

As part of the Uzazi Uzima project being implemented in Simiyu, Tanzania, we are partnering with WomenChoice Industries – a social enterprise that make reusable menstrual pads called Salama pads. Together, we are working to improve access to affordable menstrual pads. The Salama pad is a reusable menstrual pad that can withstand approximately 100 washes. This is a more affordable alternative for women who cannot afford the regular purchase of disposable pads. WomenChoice manufactures the reusable menstrual pads in Tanga, and then distributes them to vendors in Tanga and Arusha, who go on to sell them in their communities.

As part of the Uzazi Uzima project, WomenChoice will be expanding to Simiyu Region to sell the products so that the women in Simiyu have an affordable alternative. In order to understand some of the issues surrounding menstrual hygiene, and the vision behind this social enterprise, I spoke with their founder and CEO, Lucy Odiwa.

For Lucy, like many other women, her story starts with her first experience with menstruation.

Lucy Odiwa (LO): When I was in Form 3 in Asumbi Girls’ High School In Western Kenya an all girls school, at the age of 16, I was a very confident student. I remember one day I stood up to answer a question in my mathematics class. While answering I realized that my classmates were giggling and murmuring and one girl told me to sit down because my skirt was soiled. I ran out of the classroom to my dorm and was confused about what was happening to me. I was too afraid to ask other girls what to do so pulled a fellow student’s pair of socks I found hanged on the clothes line and used it as my first sanitary pad. My teachers never taught me about periods, and it was something that everyone was very shy about. The next day I realized that the clothing was not enough fabric for me, so I used a bed sheet which leaked further and I was so embarrassed that I said I wouldn’t go to class until my period finished. When I went home for the holidays, I told my family that I needed sanitary towels, but my family could only afford two packs. So, I would use them for as long as possible and use clothes at nighttime. I did this throughout secondary school and college, and it was evident that I couldn’t afford sanitary towels and needed to find a different option.

I eventually started working at a hospital as a Clinical Officer where I met girls who were complaining about their reproductive systems. They often were experiencing health problems as a result of poor menstrual hygiene management. These girls (and boys) were receiving information on myths and taboos surrounding puberty but did not know about menstrual hygiene management. So, in my spare time I started teaching girls about it.

JV: How did you decide to develop a reusable menstrual product?

LO: I wanted to go beyond teaching – I wanted to give them the right products. I wanted a long-lasting solution for those who cannot afford many packs of pads. That’s what made me think of the reusable pad. Girls were admitting to me that they would stay home from school and engage in sexual activity as a result of their periods. They were at risk for STIs, teen pregnancy, and other issues just because they couldn’t access sanitary towels.

I had about $75 USD and I started purchasing cheap fabric that was absorbent. I partnered with someone who was passionate about women’s empowerment and we developed the social enterprise model that manufactures low-cost reusable sanitary towels.

JV: Can you tell me a bit more about how you have seen menstruation affecting a young girl’s confidence?

LO: Girls have been taught that periods are shameful. There is often a scare technique – they got their period due to sexual activity or they did something wrong. It shapes their minds that something is wrong and should be kept secret. But when it is kept secret, and someone experiences leaking like I did, it destroys your confidence. I noticed my confidence was affected after that day when all my classmates laughed at me. Nobody asked me what happened to me or supported me, I had to ask these questions myself and find my own solution.

I met a girl who used a rag to manage her period, and it once fell out of her pants while she was at the market. People started heckling her and she was so ashamed that she never walked down that road again. The information they are given or the experience they have had is what kills the confidence of girls. They will isolate themselves and stop engaging in activities.

JV: I know that part of the social enterprise is that women become vendors who are trained and then sell the reusable pads in their community. Who is an ideal vendor for the product?

LO: We target girls and women who have been stigmatized or isolated in their community but have potential. When a girl becomes pregnant, she is not permitted to return to school [in Tanzania]. So, we target out-of-school girls who need business and financial skills, independent women who want to take up other business opportunities, single mothers, women living with HIV/AIDS, and sex workers who want to reduce their dependence on sex for money. I’ve seen how women who are living with HIV are strong and energetic women who learn about the illness and then become strong advocates in their community. I’ve seen how uniquely approachable commercial sex workers are. These are the types of women who have potential to become leaders with the right skills. We want to help them improve their lives by training them in business so that they can vend our products.

JV: How do you connect to these women?

LO: We have a multifaceted approach. In Tanzania, pregnant women must register with a Community Health Worker (CHW). The CHWs in urban and rural areas are the ones who know the sex workers, HIV positive women, and the out-of-school teen mothers. We also work with Village or Ward Executive Officers who know vulnerable girls in their community. We also work with government officials like Social Welfare Officers or Community Development Officers (also known as Afisa maendeleo) who interact with youth. Through these entry points we analyze the data and invite these women to participate in the training.

JV: What is the feedback of women who have participated in this model?

LO: In Tanga, [Tanzania] there was a lady who wanted to become a vendor, but she was illiterate. We normally require literacy for vendors as they will be doing some accounting. She was so determined to participate that she brought her daughter so that her daughter could help with record keeping. Our production has slowed down since COVID-19 spread, but we are still seeing an increase in orders. This shows me that the women are enjoying the product. We haven’t had any dropouts of vendors so far which makes me think that they are eager to continue.

JV: How has COVID-19 affected the enterprise?

LO: Looking at the situation, I’m trying to be empathetic with society at large. During this pandemic we are talking as if periods have stopped – but they do not stop despite a pandemic. I want to encourage anyone who is working in menstrual hygiene management to find safe ways of continuing the noble work that they have been doing. Schools and social gatherings are an easy platform to reach girls and women. We now need to think of safe, new, ways to interact with the community. If we can find safe ways to distribute PPE, then we can also find safe ways to reach girls.

I recently spoke with a girl in Tanga who told me that she wanted a reusable pad because her family could no longer afford disposable ones. Girls are sacrificing their menstrual needs for the need of the family. They’re doing it in isolation, and no one can share. We are projecting an economic crisis but there is already a health crisis happening. It might get worse, so we need to continue to find new ways to use reusable products that have long lasting effects, and new ways to reach girls safely. Because we don’t know how long this will last and who will take care of these girls.

Amref Health Africa’s partnership with WomenChoice Industries is an activity of the four-year Uzazi Uzima project in Simiyu Region, Tanzania, a partnership among Amref Health Africa, Marie Stopes and the Government of the United Republic of Tanzania, with Deloitte as a service partner. Uzazi Uzima (Kiswahili for “Safe Deliveries”) receives financial support from the Government of Canada through Global Affairs Canada and from James Percy Foundation.